From Graffiti to Gentrification: The Rise and Fall of Ghent's Concrete Playground

| Date: | 06 May 2024 |

| Author: | Bart Popken |

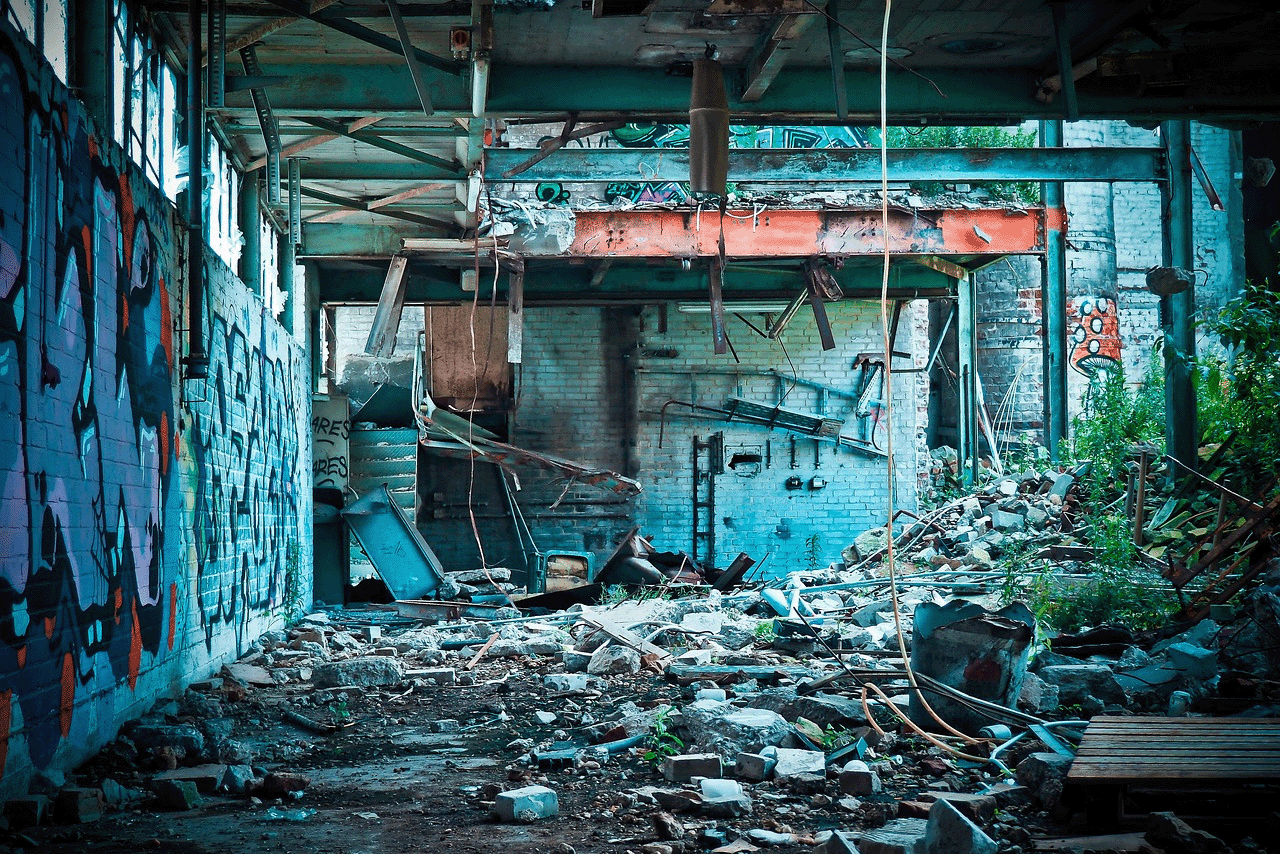

In the heart of Ghent's harbor area Oude Dokken (Old Docks) lies the Inter-Beton Concrete Factory, a site that has been targeted for urban renewal. As the city experienced difficulties with finalizing its redevelopment plans, the factory and surroundings remained largely deserted and unused. For over a decade, artists have been reappropriating the functionally indeterminate site into a meaningful place. What emerged was a melting pot of creativity, where local artists came together to express themselves through graffiti and other playful artistic activities. The factory turned into a ‘Concrete Playground’ and served as a platform for artists to hone their skills and connect with like-minded individuals. Yet, with the birth of the neoliberal creative city idea, there have been attempts to use culture and creativity to achieve non-cultural ends which are mostly economic. This one-sided emphasis seems to mask rather than reduce urban inequalities. Creative placemaking strategies have used creativity as a tool to get rid of unsanctioned activities and promote gentrification of the area. This led to the factory being demolished to make way for an upscale, residential neighborhood: Nieuwe Dokken (New Docks). What developed into a common space for artists ultimately succumbed to the effective integration of cultural festivals, mediatization and market economies. The fate of the factory serves as a reminder of the fleeting nature of non-regulated creative spaces in the face of neoliberal urban expansion.

Placemaking is becoming pervasive in language and scholarly work on urban planning. Many agencies, including municipal governments, non-profit organizations and neighborhood commissions inject placemaking elements into their city to revitalize public spaces. Some good examples of placemaking interventions are pop-up events, closing main streets for cars to open up opportunities for play, cultural festivals, street art events, temporary art installations and many more. The intention to animate stems from the recognition that public space needs continuous place-making throughout its lifespan and that its meaning derives from more than its material form (Colomb, 2012). These efforts invite people to act in playful ways to challenge and interrupt the mundane practices of community life.

On the one hand, placemaking efforts encourages people to reclaim ownership over urban space. It includes citizens taking up a performative role in the making of their city by intervening in urban systems to alter how urban spaces are used and understood (Sharpe & Glover, 2020). Such initiatives are often initiated by grassroot citizens who work together in broader social movements to transform spaces according to their own needs (Mould, 2014; Mayer, 2015). On the other hand, placemaking interventions can be used as a political tool to engender neoliberal urban development rather than a means of empowering socially, economically and politically excluded groups (Mould, 2014). The latter viewpoint looks at places that are not directly economically contributing to the urban fabric as underutilized and treats them as empty of meaning ready to be made more meaningful through placemaking (Moran & Berbary, 2021).

With this blogpost, I intend to illustrate how placemaking can be seen as a process of unmaking. While conducting fieldwork for my Master Thesis in Ghent, I found that many placemaking efforts have the tendency to overwrite local histories and overlook community needs. Walking interviews with street artists led me to discover unique stories about urban transformation in Ghent. While walking through the researched environment, certain artworks or places within the city provoked unique responses tied to their personal experiences. I want to highlight one of them: the rise and fall of a Concrete Factory in Ghent's harbor area. This story shows that a vibrant graffiti art and collaborative spirit that once defined the space, have vanished as the area became commodified for urban development and tourism. It illustrates how an art form once associated with underground culture and illegality is now finding support from real estate developers and corporate players.

Introducing the Concrete Playground

The Inter-Beton concrete factory located at Oude Dokken (Old Docks), a neighborhood in the harbor area of Ghent, had to cease its operations around the turn of the millennium. Not long after the company ceased operations, the site had been completely abandoned as the municipality had not been able to develop a destination plan. Artists told me that the beauty of urban decay and other aesthetic qualities holds their attraction and makes them act as urban explorers by discovering deserted places to paint. Therefore, Ghent’s underground community took matters into their own hands after a prolonged state of uncertainty and started occupying the neglected area, transforming it into an interesting liminal space. The site has been known for the active cooperation between a wide variety of people with all kinds of crafts which led to a vibrant place.

The Concrete Factory has been regarded by local artists as a creative playground. The artists that I interviewed addressed that these graffiti artworks did not always get the same attention as artworks located directly in the city center. In spite of this, the creative possibilities of this space were perceived as tremendous. Large factory surfaces challenged artists in their playful practices, giving them an extra creative impulse. Graffiti tags were roaming free and the empty silos and crumbling stairwells became an integral part of the urban atmosphere. For many artists, meeting up with other artists and working in the same space is part of the joy of painting. Inspiration flowed from one artist to the next as part of the spontaneous process of creativity and play. Painting at the Concrete Factory meant that artists could develop their skills and competencies. Among some of the first local artists painting at the Concrete Factory were Bué The Warrior, ROA, Phase, Sam Scarpulla and Resto who later became pioneers in the global street art scene (Langeraert et al., 2022).

Creative Placemaking and Gentrification

With the birth of the creative city, town governments and urban development agencies started to institutionalize creative practices by using initiatives of counter-cultural actors (such as graffiti artists) for their own purposes. When Ghent officially joined the UNESCO Creative Cities Network in 2009, the municipality started to develop a mission to ‘harness all creative forces in the city, to increase opportunities’ (Anheier & Isar, 2012 p. 129). Ghent's creative placemaking initiatives embody the mission of the municipality which is best reflected by the annual Sorry Not Sorry (SNS) street art festival. This placemaking event focuses on revitalizing neighborhoods in declining areas by promoting urban creativity, social engagement and cultural expression. The second and third editions of SNS were targeted to the Concrete Playground site. This aligns with Ghent's broader commitment to promote urban art in stigmatized areas.

Creative cities have one common feature: they all rely on instrumental policies that attempt to use culture and creativity to achieve non-cultural ends which are mostly economic. The colorful murals attract tourists who make pictures of the beautified environment and journalists who extensively cover them in articles resulting in an increase of attention that such districts receive. Signaling the value of place through digital platforms works mainly to attract new visitors who broadcast their own participation in the street art trend (Polson, 2024). In the case of Oude Dokken, a neighborhood that suddenly enjoys a high concentration of street art, digital media such as Instagram and Pinterest make the murals permanently accessible thereby contesting their ephemeral nature.

Not only hip urbanites and tourists follow social media feeds, real estate developers and financial speculators are paying attention as well. The new data-driven industries help these actors through digital media to predict where real estate prices will increase and which neighborhoods are rife for investment (Stewart, 2019; Polson, 2024). This artwashing describes how new corporate developments and urban municipalities use commissioned street art to co-opt creativity that lends ‘streetness and coolness’ to the urban area (Polson, 2024). Thus, with increased digital embeddedness of an art form that once was associated with underground culture and illegality, we are now witnessing a transformation in support of real estate development and corporate interests.

Placemaking as unmaking?

Placemaking projects are often criticized for tweaking the purpose of participation to encourage the activation of places rather than focusing on political emancipation. By deliberately choosing renowned international artists over local artists, the SNS festivals succeeded in generating significant media attention. This attracted more visitors to Oude Dokken and enhanced its symbolic value (Polson, 2024). While this elevated the economic potential of the area, the original contributions of counter-cultural artists to the area had been overshadowed.

Whereas the municipality guarantees inclusivity of the new neighbourhood, various real estate websites portray a different story showing astronomical housing prices. Only 20% of the realized housing will become social housing which is moreover seen by the developers as the least prioritized element in the project (Casteels, 2022). Without dedicated spaces for artists to work and live, a neighborhood with rising real estate values is very unlikely to sustain its artists population. Artists are thus regarded as ‘pawns in the redevelopment game’ (Leeson, 2019) as they are driven out once the neighborhood starts to get more economically viable from their creative activities.

With this blogpost, I have attempted to show that every form of placemaking is always an unmaking of something. These unmakings perpetuate socio-economic injustices under the pretense of a collaborative and participatory process. The unmaking of the Concrete Playground at Oude Dokken reminds us of the need to ensure that placemaking efforts do not erode the social and cultural histories that give neighborhoods their unique character. Therefore, we must always ask ourselves which people placemaking is for? And if it isn’t for all people, isn’t it just a more palatable word for gentrification?

This text has been crafted by Bart Popken, lecturer Human Geography and Planning at the University of Groningen. As of last year, Bart wrote a blogpost for the Human Geography and Spatial Planning blog about squatting practices in Amsterdam . In this blogpost, he explores the relationships between placemaking and gentrification in Ghent. The story of the Concrete Factory unfolded after two months of ethnographic fieldwork with street artists, place-makers and municipal authorities in Oude Dokken. In the near future, Bart aims to expand his scholarly work on themes like gentrification, placemaking and creative city policies.

Sources

Anheier, H. K., & Isar, Y. R. (Eds.). (2012). Cultures and globalization: cities, cultural policy and governance. Sage.

Casteels. (2022).Herontwikkeling van de Oude Dokken in Gent, echt voor iedereen? – Archined. https://www.archined.nl/2022/09/herontwikkeling-de-oude-dokken-in-gent-echt-voor-iedere en/

Colomb, C. (2012). Pushing the urban frontier: Temporary uses of space, city marketing, and the creative city discourse in 2000s Berlin. Journal of urban affairs, 34(2), 131-152.

Langeraert, H., Manco, T., Riva, G., & Van Melkebeke, D. (2022). Concrete Playground: In Memory of Betoncentrale Ghent: Street Art Over the Years. Lannoo.

Leeson, L. (2019). Our land: creative approaches to the redevelopment of London’s Docklands. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 25(4), 365-379.

Mayer, J. (2015). Cities in the Making: Social Movements, Neo-Liberal Urbanism and Critical Practies. A Conversation With Margit Mayer. Diffractions, (5), 1-14.

Moran, R., & Berbary, L. A. (2022). Placemaking as unmaking: Settler colonialism, gentrification, and the myth of “revitalized” urban spaces. In Leisure Myths and Mythmaking (pp. 106-120). Routledge.

Mould, O. (2014). Tactical urbanism: The new vernacular of the creative city. Geography compass, 8(8), 529-539.

Polson, E. (2024). From the tag to the# hashtag: Street art, Instagram, and gentrification. Space and Culture, 27(1), 79-93.

Stewart, M. (2019). The real estate sector is using algorithms to work out the best places to gentrify. Failed Architecture. https://failedarchitecture.com/the-extractive-growth-of-artificiallyintelligent-real-estate/

Sharpe, E. K., & Glover, T. D. (2020). Placemaking in the playful city: Playing in and playing with the urban environment. In Leisure communities (pp. 91-99). Routledge.

Zitcer, A. (2020). Making up creative placemaking. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 40(3), 278-288.